When Conviction Trumps Evidence

Lessons of a measles outbreak

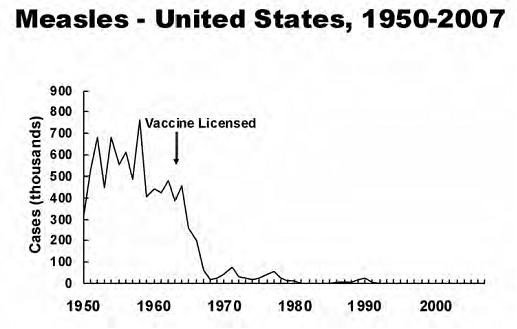

Before 1963, almost all children got measles in the United States. Decades later some remember it as a rite of passage, unpleasant certainly, but not a terrible event. But memories deceive. In 1962, according to the Centers for Disease Control, about 450,000 American children got measles and 450 of them died, while perhaps 20% had serious complications like pneumonia, ear infections, and encephalitis. Before the first measles vaccine was licensed in 1963, nearly 50,000 children were hospitalized each year. Measles caused misery and forced school absences; parents could not work, while physicians and hospitals were preoccupied with a very contagious disease.

What happened after an effective vaccine was introduced? In a few years the disease almost disappeared, as the graph shows. Similar graphs could be shown for diphtheria in the 1930s, for polio in the 1950s, for measles, German measles and mumps in the 1960s, and chicken pox in the 1990s. We now have a combined vaccine for measles, mumps, rubella and chicken pox, given at 12-15 months and from 4-6 years old, prior to school. More than 95% of children are protected for these and other common infectious diseases.

The Centers for Disease Control: www.vaccines.gov. This website describes similar declines in disease following the introduction of many vaccines.

All of this makes me wonder why some educated parents refuse to vaccinate their children. In California’s Marin County, almost half of the kindergarten students in some schools are not vaccinated. Perhaps it is a fear that vaccines cause autism, an idea that has been discredited. The scientific paper from the 1990s that purported to show a link is fraudulent, and the physician who wrote the paper has been “struck off” as the British artfully put it. The problem here and in other cases, is that conviction trumps evidence. Spokespeople like Jenny McCarthy insist that vaccines cause autism, which is just wrong. Senator Rand Paul, (did he really go to medical school?) recently repeated this foolishness. As a result, we have had outbreaks of measles from which children have died, outbreaks of mumps, and also of whooping cough, as described in these pages by my pediatrician colleague Dr. Adam Ratner (link).

These are good parents who see to their children’s nutrition. The kids will probably not be obese or have vitamin deficiencies. But these children will still be vulnerable to poliovirus in the gut or measles virus in the nasal passages or dozens of other afflictions. Worse, they will spread it to children who are too young to have been vaccinated or who are immune-compromised, as a result of cancer treatment or transplants, or other reasons. This is what recently happened at Disneyland when a single infectious child started a measles epidemic that spread through California and the country.

The polio and measles viruses do not care how healthy you are (forgive the anthropomorphism.). Viruses are machine-like parasites that hijack a victim’s cells and cause serious disease. One infected cell can produce hundreds of viruses and the infection spreads exponentially in the body, causing inflammation and damage, until the antibodies of the immune system catch up with the infection. It is not a given, as we learned during the Ebola epidemic, that the patient’s immune system, which takes time to mount a response, will win the race.

Parents may have other reasons for hesitating about vaccines. There is an old idea – going back to the origin of the smallpox vaccine in 1803, that it is absurd to put a foreign object into a healthy body. Some people still believe that vaccines can cause the disease, which is not true. Vaccines use weakened viruses (the Sabin polio vaccine) or dead ones (the Salk polio vaccine), and while they are all designed to provoke the immune system, they do not cause disease.

One mother, whose comments I read on-line, wrote that her child had easily “fought off” a vaccination with no ill effects and she did not understand why he could not have done the same to an actual infection. She does not understand how the immune system works. An unvaccinated two-year old has billions of lymphocytes, the cells that make antibodies, but only a few that make antibodies to neutralize the measles (or any other) virus). This is not enough to block an infection. When a child is vaccinated, the few lymphocytes that recognize the inactivated measles virus undergo an astonishing change and start to divide – one will make two, two will divide to become four and in two weeks that child will have millions of specific lymphocytes making antibodies that trap the invading virus. After the threat has passed, many of the vaccination-induced lymphocytes persist, sometimes for life. Whenever the threatening virus appears, even years later, the child or adult is prepared and the virus does not stand a chance. General Colin Powell once said about military battles that we don’t want them to be a fair fight. We want to win quickly. He could have been talking about viruses and vaccines.

Richard Kessin, Ph.D, is Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. He and his wife Galene live in Norfolk. He can be contacted at rhk2@columbia.edu.