The Body Scientific

March 7, 2024

Measles Again!

But Why?

Richard Kessin

The measles vaccine was licensed in 1963. It is a live attenuated virus vaccine that provides lifelong protection with few side effects. The virus is extraordinarily contagious. It does not cause autism. The measles vaccine is usually given with mumps and rubella vaccines, and now with the chicken pox vaccine. With earlier vaccines for whooping cough, tetanus, and diphtheria, and in the 1950’s, polio, life for children and parents became less fearful.

But let’s go back to 1963, when every child in the United States and across the world got measles. It caused them true misery. There were about 600,000 cases in children in 1963 in the United States. People my age (old) will sometimes say, “I had measles, and it was no big deal, it was uncomfortable, and I had a fever, and all those spots scared my Mom, but I got over it.” This sort of extrapolation is dangerous because humans are not genetically identical, and our immune systems vary—for 20% children and their parents, measles was a very big deal; they had complications, usually encephalitis, an infection of the brain, pneumonia, or ear infections. In 1963, about 120,000 children were hospitalized in the US, and about 400 died.

Measles is a respiratory disease; we inhale virus particles, and they infect cells of the trachea and upper lung. They go on to infect immune cells, which carry the virus to all parts of the body, including the skin where the spots appear. Usually, the spots start in the scalp and then appear on the face, the trunk, and extremities in that order. It has an incubation period of weeks and takes some time to get over. Measles is common in other parts of the world; it is still a killer in Africa and Asia.

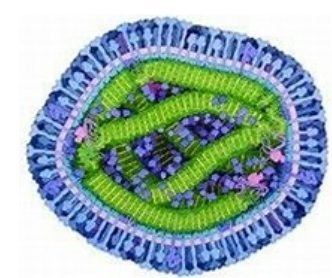

The measles virus is made of RNA, which differs slightly from DNA. Many other nasty viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, Ebola, and polio are made of RNA. The measles virus genome is about half the size of SARS-CoV-2, and only has six genes. The human genome is 3.2 billion nucleotides, a million times more that this virus. The virus is small, but potent. One of its powers is to defeat the defenses of an unvaccinated host.

We have two immune systems: innate and adaptive. The much older innate system is the first point of contact with a virus, and it has many tools to slow an infection, but only if it recognizes the virus RNA, its genetic material. The measles virus has incorporated into its tiny genome instructions to make an enzyme, or catalyst, called adenosine deaminase, which removes a nitrogen atom and a couple of hydrogens from adenosine components of the virus genetic material. That makes the virus invisible to the innate immune system, but the virus can still make thousands of copies of itself. The innate immune system has many tools to fight infections, but with measles, the virus hides in plain sight.

Imagine an unvaccinated child with a case of measles. The child survives, but impairment of the innate immune system lasts several years. The measles virus affects the antibodies that react against other diseases that the child has already survived. Without that protection, old but latent infections—say hepatitis or malaria, can be reawakened and new virus infections become more dangerous. What measles research tells us goes beyond measles.

The measles virus evolved (perhaps a thousand years ago) from a cattle virus called Rinderpest, to which it remains similar. Rinderpest virus has been eliminated from cattle through vaccination. (The only other virus to be eliminated was smallpox). In 2000, the United States was sufficiently vaccinated that no cases of measles were recorded. The excellence of the vaccine and experience with Rinderpest led to the idea of eliminating the measles virus, but a decline in vaccine acceptance after a false autism scare, ended that hope. We now have periodic outbreaks of measles, usually from isolated communities. CDC is trying to suppress an outbreak in Chicago now. These cases are indicators that the public health system has deteriorated, often for ideological reasons, as is now the case in Florida. The numbers change daily, but a recent one was one hundred cases in the United States; significantly half of these kids were in the hospital, meaning they were quite sick.. Measles infections are a harbinger, or a canary in a coal mine. The Florida health authorities in not requiring vaccination, are deluded. If for measles, what else? Perhaps mumps, rubella, and chickenpox to which the vaccine also provides protection.

Richard Kessin, PhD is Emeritus Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Figure 1: The measles virus, showing the RNA genetic material (green) that provides instructions for human cells to make specific virus proteins. The spots of measles appear toward the end of the infection. The virus only infects humans and 58 cases have occurred so far in the US this year (now 100 and climbing. From the CDC image library.